by Pat Lowinger

The earliest ‘historians’ of the Mediterranean were Greek and as such they serve as both a template and warning for modern Historiography. From the eighth through sixth centuries BCE, various Greek city-states grew and prospered. In turn, these city-states founded numerous colonies throughout the Mediterranean which brought the Greeks into contact with previously unknown lands and cultures. As the Greeks continued to explore and colonize even more remote parts of the Mediterranean, many of these explorers (and colonists) began to record the geography, cultures and histories of themselves (as foundation cults) and those they encountered.[1] This desire of the Greeks to create these records and preserve them for themselves and future generations- as well to aggrandize the accomplishments of Greek culture is the spark which ignited Greek Historiography and laid the foundations for subsequent historical traditions.

The Greek World

Map of the ‘known world’ based on the accounts of Herodotus. Original map published by Hatchett & Co. 1884. Click to expand.

The Greek city-state (polis) emerged during the eighth century BCE. In the simplest of terms, the polis was the city itself and surrounding country side which fell under its control.[2] This was much more than a village or town; it was a center of government formed by the unification of the populace into a body known as the politai. Members of individual poleis typically identified themselves with the polis itself (i.e. Sparta) rather than a larger cultural identifier (i.e. Greek). As previously mentioned the Greeks undertook extensive exploration and colonization efforts throughout the Mediterranean- which by the end of the fifth century BCE resulted in Greek colonies stretching from the coast of the Black Sea to Southern Spain.

As Greek civilization continued to develop during the Archaic Age, many Greeks undertook intellectual and academic pursuits. While much of these early intellectual pursuits were confined to the development of lyric poetry and philosophy, others undertook the process of categorizing and describing the known world. The vastness of the world, as the Archaic Greeks knew it, as well as their apparent mastery of it; either birthed or fostered beliefs in the superiority of themselves and of their culture. To the Greeks, the outside world was the domain of the ‘barbarians’ and lesser races of people. While various poleis competed among themselves, by the end of the sixth century BCE the Greeks found themselves in the center of a huge world, or so they believed, which was inhabited by strange, mystical and often warlike peoples.

Before Herodotus: The Homeric Epic

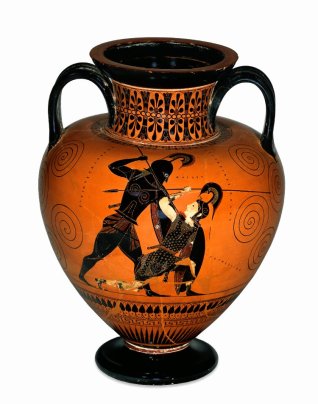

Greek amphora (c. 525 BCE) depicting the hero Achilles slaying Penthesilea. On display at the British Museum.

The beginning of Greek history as we know it owes its humble beginnings following the collapse of the Mycenaean Greece at the end of the Late Bronze Age. Whether ‘The Collapse’ was due to earthquakes, drought, or changes in militaristic organizations and weapons production- the precise cause for the collapse of these great kingdoms is still under debate by scholars.[3] Neither the Mycenaeans nor their Minoan neighbors were without written records, in fact the discovery of both the Linear A and Linear B tablets contain a wealth of information regarding Mycenaean society and culture,but the script used to make these records were undecipherable to the Greeks of the sixth century BCE. [4] This isn’t to imply that the Mycenaeans were unknown to their Dorian, Ionian and Aeolic descendants. Many of which lived in the shadow of the once great Mycenaean citadels of Knossos, Argos, Athens, Orchomenos and Mycenae. Likewise, the Egyptians and Mesopotamians had also extensive written records, but these appear to have been preserved in support of religious and/or bureaucratic functions.

In the four-hundred-year span (1200-800 BCE), commonly known as the Greek or Geometric Dark Age grew traditional stories commonly known as Homeric Epics. The Iliad and the Odyssey are perhaps two of the best known pre-Christian works of literature which emerged during this post-Mycenaean period. While custom attributes the genesis of these tales to Homer it is quite plausible these tales were derived from multiple rhapsodes.[5] Regardless of their precise origin, these epics formed the basis for many ‘Greek ideals’.

Throughout the Iliad, several themes present themselves. The first is religious, that the gods not only exist but interact and often interfere in the lives of mortal men. The second theme espouses the deeds of great men which served to demonstrate the ideals of virtue and bravery in war. The last theme is one of disgrace for cowards or cowardly behavior. The following is an example of Homer’s contempt for the coward and adoration of the hero, “The skin of the coward changes color all the time, he can’t get a grip on himself, he can’t sit still, he squats and rocks, shifting his weight from foot to foot, his heart racing, pounding insides the fellow’s ribs, his teeth chattering- he dreads some grisly death. But the skin of the brave solider never blanches.” [6]

Bust depicting Herodotus (Roman copy of Greek original), Metropolitan Museum of Art

Herodotus: The Histories

Herodotus of Halicarnassus (c. 484- 425 BCE) is known to have lived during the fifth century BCE and is often credited by his proponents as The Father of History and as The Father of Lies by his detractors.[7] While it is true that as a historian Herodotus and his Histories are not without serious concern to modern scholars, it is important to understand that his work was founded on the earlier Homeric model. The Histories were written to serve both a record and commentary of the Greco-Persian Wars which had been the major military conflict of Herodotus’ lifetime.[8] While Herodotus attempted to detail major historical events, places and peoples- he often lacked good data and was prone to occasional fabrication and/or inclusion of divine intervention. This was done not only to fill in the gaps, but to promote a dramatic flair to his historical narrative. Detractors aside, historiography, in the west is credited to have begun with Herodotus and while far from perfect, he undertook the previously unprecedented task of, at least nominally, differentiating fact from myth.[9]

After Herodotus: Thucydides and Xenophon

Bust depicting Thucydides (Roman copy of Greek original), Pushkin Museum.

Thucydides (460-400 BCE) was a contemporary of Herodotus, but whose own work seems to have been built upon the best precepts of the Histories. Unlike Herodotus, Thucydides was not only an observer, but was a participant in the history which he recorded- serving as a general in the army of Athens. What is initially obvious to the reader of both works is that Thucydides’ style and organization is very different from Herodotus. Rather than a post-facto account, major portions of Thucydides’ The Peloponnesian War appear to have been written as major events unfolded- in painstakingly chronological order. Those parts which were written afterwards appear to have been completed within a year or two after to conflict had concluded. According to historian Victor David Hanson, “what stands out about Thucydides is not his weakness but his strengths as a historian. We note his omissions, but no account of the Peloponnesian War or of fifth-century Greece in general is more complete.” [10] Even so, Thucydides’ history is not without its own problems regarding a lack of crediting his sources and details very few non-militarily related incidents.[11]

Xenophon (c. 430-354 BCE), like Thucydides was an Athenian general. Yet, unlike Thucydides, Xenophon traveled extensively into Anatolia and Persia as detailed in the Anabasis and the Cyropaedia. Xenophon also wrote extensively on the Constitution of Sparta, a detailed biography of the Spartan King, Agesilaus II and the Hellenica which details the history following the Peloponnesian Wars until approximately 360 BCE. As with his predecessors, Xenophon’s style is unique, but more closely related to Thucydides, than Herodotus- but like his fellow Athenian also fails to cite his sources. Even so, most historians agree that Xenophon’s accounts are much more credible that Herodotus’, appearing to have either been an eye-witness to events or been only one or two persons removed. [12] As with all early sources, Xenophon’s work shows significant problems, not the least of which is his pro-Spartan bias and his factual misrepresentation of certain historical events.

Conclusion

Greek Historiography grew as a natural extension of the Homeric epic and the need within the culture of ancient Greece to superiority of their history to those of others. History was not only an academic pursuit; it was a matter of cultural identity. The ancient Greeks saw themselves as both intellectually and morally superior than those people(s) and cultures surrounding them. While the concept of nationalism was unknown to the early Greeks, this collective history often bound them in common purpose as seen during the Greco-Persian Wars.

From its humble beginnings with Herodotus, within just two generations a vibrant tradition of creating historical records was alive and flourishing within the Greek world. While no means perfect, there appears to have been an ever-increasing self-imposed obligation to records as many verifiable facts as possible and to distinguish those facts from that which was merely speculation or founded upon myth. This tradition would continue through the later Hellenistic and into the Roman period. The discipline of history had been born.

Bibliography & Citations:

Breisach, Ernst. Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, & Modern. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007.

Brouwers, Josho. Henchmen of Ares: Warriors and Warfare in Early Greece. Rotterdam: Karwansaray Publishers, 2013.

Drews, Robert. The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993.

Herodotus, and Aubrey De Sélincourt. The Histories: Herodotus. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1981.

Homer, and E. V. Rieu. The Iliad: By Homer. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1950.

Howell, Martha C., and Walter Prevenier. From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001.

Marincola, John (editor) & various contributors. A Companion to Greek and Roman Historiography. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, 2011.

Pipes, David. “Herodotus: Father of History, Father of Lies.” Loyola University New Orleans. Accessed October 01, 2015. http://www.loyno.edu/~history/journal/1998-9/Pipes.htm

Palmer, Leonard R. The Interpretation of Mycenaean Greek Texts. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969.

Pomeroy, Sarah B. Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. 3rd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

Thucydides, and Robert B. Strassler. The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian Wars. New York, NY: Simon Et Schuster, 2008.

Xenophon, John Marincola, and Robert B. Strassler. The Landmark Xenophon’s Hellenika: A New Translation. New York: Pantheon Books, 2009.

[1] Breisach, Ernst. Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, & Modern. 3rd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 9.

[2] Pomeroy, Sarah B. Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. 3rd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 104-105.

[3] Drews, Robert. The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe Ca. 1200 B.C. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1993), 175-208.

[4] Palmer, Leonard R. The Interpretation of Mycenaean Greek Texts. (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1969), 60-62.

[5] Breisach, Ernst. Historiography: Ancient, Medieval, & Modern. 3rd ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), 5.

[6] Homer, and E. V. Rieu. The Iliad: By Homer. (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1950), 350.

[7] Pipes, David. “Herodotus: Father of History, Father of Lies.” Loyola University New Orleans.

[8] Brouwers, Josho. Henchmen of Ares: Warriors and Warfare in Early Greece. (Rotterdam: Karwansaray Publishers, 2013)

[9] Howell, Martha C., and Walter Prevenier. From Reliable Sources: An Introduction to Historical Methods. (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2001), 4-5.

[10] Thucydides, and Robert B. Strassler. The Landmark Thucydides: A Comprehensive Guide to the Peloponnesian Wars. (New York, NY: Simon Et Schuster, 2008), xxii.

[11] Leone Porciani and John Marincola (editor). A Companion to Greek and Roman Historiography. (Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, 2011), 328-334.

[12] Xenophon, John Marincola, and Robert B. Strassler. The Landmark Xenophon’s Hellenika: A New Translation. (New York: Pantheon Books, 2009), lix.

Two questions:

1) What was the purpose of these histories? Were they intended as money-making enterprises, were they “vanity projects,” or political polemics intended to smear rivals while glorifying the author?

2) Do we know who the supposed “consumers” of these historical accounts were (e.g. who were the audience the works were written for)?

LikeLike

The ‘purpose’ of the histories, in general, was to preserve and transmit what were seen as the great events of Greek history. Since the ‘histories’ originate from a tradition of various lyric poetry and Homer’s Iliad, the style was much more verbose than what we might consider ‘wholly’ factual today. From the late Archaic and into the early Classical period there was a shift in Greek thought- among the growing class of ‘intellectuals’ who desired to explore, categorize, evaluate and record the histories, lands and cultures of the known world. At this early genesis there was a marked attempt (which grew) to parse fact from fiction…history from myth. Without a doubt, a pro-Greek bias is pervasive, but in the Mediterranean this is the first ‘academic’ attempt to preserve history. This stands in stark contrast to the religious-royal archives of many earlier civilizations.

As far as ‘consumers’ go, the histories were intended to serve as a record to be read by both in their own time and by future generations. In Book One of Herodotus’- The Histories he writes, “…so that human achievements may not he forgotten in time, and great and marvelous deeds- some displayed by the Greeks, some by the barbarians- may not be without their glory; and especially to show why the two people fought with [against] each other.” Initally, histories were intended for those who could read, or had access to literate men of the age. As literacy rates increased throughout Greece during the Classical period, so to did the audience who had direct (and indirect) access to them. As for the works of Herodotus, The Histories became one of the primary instructional texts of its day and continued as such throughout the Classical and Hellenistic periods.

LikeLike